Finding Your Roots

Finding My Roots

Season 11 Episode 10 | 52m 10sVideo has Closed Captions

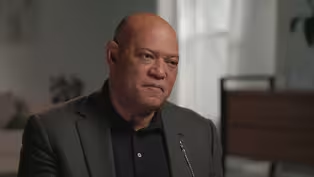

Family mysteries are solved for actor Laurence Fishburne & scholar Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

In a unique and highly emotional episode, actor Laurence Fishburne is joined by scholar Henry Louis Gates, Jr.—who finds himself a guest on his own show for the first time. Both men have been haunted by profound family mysteries for years. Cutting-edge DNA detective work will solve those mysteries—introducing Laurence and Henry to ancestors whose names they have longed to hear.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Corporate support for Season 11 of FINDING YOUR ROOTS WITH HENRY LOUIS GATES, JR. is provided by Gilead Sciences, Inc., Ancestry® and Johnson & Johnson. Major support is provided by...

Finding Your Roots

Finding My Roots

Season 11 Episode 10 | 52m 10sVideo has Closed Captions

In a unique and highly emotional episode, actor Laurence Fishburne is joined by scholar Henry Louis Gates, Jr.—who finds himself a guest on his own show for the first time. Both men have been haunted by profound family mysteries for years. Cutting-edge DNA detective work will solve those mysteries—introducing Laurence and Henry to ancestors whose names they have longed to hear.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Finding Your Roots

Finding Your Roots is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

Explore More Finding Your Roots

A new season of Finding Your Roots is premiering January 7th! Stream now past episodes and tune in to PBS on Tuesdays at 8/7 for all-new episodes as renowned scholar Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. guides influential guests into their roots, uncovering deep secrets, hidden identities and lost ancestors.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipGATES: I am Henry Louis Gates Jr.

Welcome to "Finding Your Roots."

In this episode, we'll search for the biological father of actor Laurence Fishburne.

FISHBURNE: I'm on the edge of my seat here.

I've waited 60 some odd years for this.

GATES: Then I myself will sit down with genetic genealogist, CeCe Moore, and investigate a mystery that's haunted my family for generations.

MOORE: Here's your Book of Life.

GATES: Oh my goodness.

I never thought I'd see one of these.

To uncover our roots, our team has used every tool available.

Genealogists comb through paper trails, stretching back hundreds of years.

FISHBURNE: This is great.

GATES: While DNA experts utilize the latest advances in genetic analysis to reveal secrets that have lain hidden for generations.

FISHBURNE: Whoa, that's what I'm talking about.

GATES: And we've compiled it all into a Book of Life, a record of all of our discoveries.

FISHBURNE: Wow.

GATES: And a window into the hidden past.

You just met your half-siblings.

FISHBURNE: Oh my God, that's crazy.

MOORE: Did you ever imagine you would see this?

GATES: No, never.

MOORE: How are you feeling?

GATES: This is so deeply moving.

I mean, stunningly powerful.

FISHBURNE: It's better than any movie script or television play I've ever read.

(laughing).

GATES: Laurence and I are about to embark on journeys that would have been impossible to make even a decade ago.

But thanks to DNA detective work, we're going to hear the names of ancestors we have long dreamed of hearing.

We're going to see for the very first time where our roots really lie.

(theme music playing).

♪ ♪ (book closes).

♪ ♪ GATES: There's a revolution happening right now.

DNA analysis is transforming genealogy.

Uncovering long lost relationships and changing everything we know about our roots and our kin.

In this episode, we're going to watch this revolution unfold in two family trees, Laurence Fishburne's, and my own.

We'll start with Laurence's.

Although he's recognized all over the world, Laurence came to me with a fundamental question about who he actually is.

FISHBURNE: My question really concerns my origins.

I, you know, all my life up until the time I was about 49 years old.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

FISHBURNE: I was led to believe that a man named Laurence John Fishburne Jr. was my biological father, and he was my dad, he showed up, gave me his name, um, but that's not true.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

FISHBURNE: He is not my biological father.

And really, I'd like to know who that person is, if that person exists.

GATES: There was only one way to help Laurence, DNA.

So I reached out to my friend and colleague, genetic genealogist CeCe Moore.

CeCe has solved more DNA mysteries than anyone I know, and she was not fazed by this one.

She started with Laurence's, Y-DNA, the type of DNA that a man inherits from his direct paternal line.

It's passed virtually intact from father to son down through the generations, meaning that two men with matching Y-DNA will often share the same last name.

And this gave us our first big clue.

You ready to see what we found?

FISHBURNE: I am.

GATES: Would you please turn the page?

FISHBURNE: Sure.

GATES: Laurence, this graphic lists the surname that most frequently matches your Y-DNA signature, and thus that of your biological father.

Would you please read the surname right there out loud?

FISHBURNE: Bohannan.

GATES: Bohannan.

FISHBURNE: Bohannan, huh?

GATES: Have you ever heard that name mentioned in your family and associated with your mother or cousins or anything?

FISHBURNE: No, no, mm-mm.

GATES: Well, biologically that is your surname.

So all this time you have been Laurence Bohannan pretending to be... People take stage names.

FISHBURNE: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

I'm Bohannan's boy, whoever Bohannan was.

GATES: You are Bohannan's boy.

FISHBURNE: Okay, okay.

GATES: With this name in mind, CeCe now focused on Laurence's autosomal, DNA, the type of DNA we inherit from both of our parents.

CeCe and our team began searching for autosomal matches that linked Laurence to other Bohannans in publicly available databases.

It was a painstaking process, but after building out the family trees of dozens of matches, we made an incredible discovery.

Would you please read the names of your father's parents?

FISHBURNE: Murvin Hilliard Bohannan.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

FISHBURNE: And Loretta Constance Sandridge.

GATES: You just met your grandmother and your grandfather.

FISHBURNE: That's just, that's just great.

GATES: You never heard those names before?

FISHBURNE: No, sir, it's wonderful.

GATES: What's to learn?

FISHBURNE: It's, it's wonderful.

It's, it's better than any movie script or television play I've ever read.

(laughing).

GATES: You have a major chunk of your DNA comes from these two.

FISHBURNE: This is amazing.

This is amazing for me.

Yeah, this is beautiful.

GATES: Since we'd identified Laurence's paternal grandparents, we knew that a son of theirs must be his biological father.

The only problem the couple had two sons, Murvin Bohannan Jr. and William Seigel Bohannan, and both men have passed away.

So we couldn't gather DNA evidence to distinguish between them.

It seemed like we'd hit a dead end, but then we got lucky.

William Bohannan has two living children, and we were able to track down one of them, a daughter named Lisa.

So we contacted Lisa and asked her to take a DNA test.

FISHBURNE: Mm-hmm.

GATES: If Murvin Jr. was your biological father, then Lisa would be your first cousin.

FISHBURNE: Mm.

GATES: But if William was your biological father, then Lisa is your half-sister.

FISHBURNE: Okay.

GATES: On the next page, I'm going to show you a chart revealing how much DNA that you and Lisa share.

FISHBURNE: Mm-hmm.

GATES: And thus your genetic connection with Lisa.

FISHBURNE: Okay.

GATES: If you share roughly 25%, then you are half-siblings.

FISHBURNE: Okay.

GATES: And you share a father.

FISHBURNE: Okay.

GATES: Okay?

FISHBURNE: Alright.

GATES: You ready?

FISHBURNE: Mm-hmm.

GATES: Please turn the page.

Would you please read the information transcribed in the white box?

FISHBURNE: Wow.

"Shared amount of DNA between Lisa Bohannan and Laurence John Fishburne III, 22% shared.

Relationship between Lisa Bohannan and Laurence John Fishburne III, half-sister, half-brother."

Wow, so that's my half-sister.

GATES: That's your half-sister.

FISHBURNE: So her dad was... GATES: Lisa's, DNA, confirmed that she is your half-sister, and that means that your biological father, turn back.

FISHBURNE: Is William... GATES: William Siegel Bohannan.

FISHBURNE: Yeah.

Okay.

GATES: The mystery is solved.

FISHBURNE: That's cool.

GATES: Now that we knew his name, we set out to find as much as we could about William's life.

Laurence, of course, was eager to see anything at all, and especially delighted by what we showed him first.

(gasps).

FISHBURNE: There he is, is that him?

Hey, Pop.

Oh my God.

Wow.

That's my dad.

GATES: That's your father.

FISHBURNE: That's cool, thank you, Skip.

GATES: What's it like finally to see his face?

FISHBURNE: It's so nice to see his face and to see him smiling.

And he's dressed well.

He's probably what, late 40s, early 50s in this photograph?

GATES: Mm-hmm, I think so.

FISHBURNE: Mm-hmm, yeah.

He looks like a kind man.

GATES: Hmm.

FISHBURNE: He looks like a kind man.

GATES: So what are you feeling right now, if I may?

FISHBURNE: Relieved.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

FISHBURNE: Relieved, yeah, yeah.

And, uh, you know, there's a certain amount of joy that I feel now.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

FISHBURNE: Yeah.

GATES: Hmm.

FISHBURNE: Because I know I come from somewhere.

GATES: Yeah.

FISHBURNE: You know?

GATES: Laurence was about to learn more about where he came from than he'd ever imagined possible as a treasure trove of documents and images, brought his father to life.

From high school photos and military service records, all the way to a funeral program that tied everything together.

FISHBURNE: "William was employed by the Belt Railway for 30 years.

He was an avid swimmer and diver.

His passion, however, was jazz.

He moonlighted as a DJ at various local radio stations and shared his music with all who'd listened.

It was this passion for jazz that sustained him and is his legacy and gift to those who loved him.

He leaves children, Lisa and William."

(laughter).

He was a jazz head.

GATES: How about that?

FISHBURNE: I'm a jazz head.

GATES: There you go.

FISHBURNE: Oh my God.

Jesus.

Jesus.

This is great.

This is, this is great.

GATES: There was still a question in front of us.

William spent much of his life in and around Chicago, but Laurence was born in Augusta, Georgia, where his mother, a woman named Hattie Crawford, was raised.

So how did William and Hattie end up together?

We found the likely answer buried in William's military records.

When Laurence was conceived, William was stationed at Fort Gordon, Georgia.

Just miles from where Hattie was working as a school teacher.

They were 10 miles apart, as you could see on that map.

FISHBURNE: That's it, 10 miles?

GATES: 10 miles you could walk.

FISHBURNE: That's a walk.

GATES: So Laurence seeing this, how do you imagine they met?

He would've been 23, your mom, about 25.

FISHBURNE: They met, hanging out.

GATES: Hanging out.

FISHBURNE: Jukin, whatever they was doing.

GATES: Yeah.

FISHBURNE: Yeah, at the soda fountain, I don't know, wherever they was at.

GATES: Well, we can't be certain, but we have a theory.

FISHBURNE: Mm-hmm.

GATES: Please turn the page.

FISHBURNE: Ooh, a theory.

I like a good theory.

GATES: This was published in "The Augusta Chronicle" on April 3rd, 1960.

Would you please read that transcribed section?

FISHBURNE: "The following activities have been announced for this week at the Ninth Street, USO.

Coffee, sacred music and church dates."

Mm, "sacred music."

GATES: Sacred music.

FISHBURNE: "10:00 A.M. to noon, singing around the piano.

5:30 P.M. Miss Hattie Crawford will be in charge."

GATES: How about that?

FISHBURNE: Uh, yeah, there you go.

There you go.

GATES: There you go.

FISHBURNE: Wow, "singing around the piano."

(laughter).

Hmm.

GATES: According to this article, Laurence's mother Hattie was a volunteer for the USO, a nonprofit organization that provides entertainment to members of the military.

And this quite likely is what put her in the company of William Bohannan for an evening, or perhaps longer, more than 60 years ago.

A realization that filled Laurence with emotion.

FISHBURNE: I'm having all the feels as they say.

(laughter).

I'm having all the feels, Skip.

I'm intrigued, I'm relieved, I'm, uh, you know, confused.

Uh, and I'm also quite alright with all of this.

GATES: Right.

FISHBURNE: I'm really alright with all of this, because it's, I don't have to speculate about it anymore.

GATES: Nope, you don't.

FISHBURNE: I don't have to speculate about it anymore.

I don't have to wonder, you know, every time I look up and think, "Oh, is it that guy?"

GATES: Yeah.

FISHBURNE: "Oh, is it that guy?"

GATES: Do you feel less like an orphan?

FISHBURNE: Yeah, absolutely.

I feel less isolated.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

FISHBURNE: And, um, other.

GATES: Yeah.

FISHBURNE: Yeah, yeah, I feel less other.

GATES: My own family mystery lies deeper in the past than Laurence's, much deeper.

But it's had a shaping influence on me just the same.

I am nervous.

And in the hopes of solving it, I've asked CeCe Moore to take my job for a day and let me be the guest.

MOORE: Skip, today we're switching things up, and I'm giving you the "Finding Your Roots" treatment.

GATES: I feel naked over here.

MOORE: Here's your Book of Life.

GATES: Oh my goodness.

I never thought I'd see one of these.

CeCe and I started with a story that I've told many times before.

It begins at the Rose Hills Cemetery in Cumberland, Maryland.

My grandfather Edward Gates, was buried here on July 2nd, 1960 when I was nine years old.

Following the funeral, my father showed my brother and me a photograph of Edward's grandmother, a woman named Jane Gates.

Jane is my great-great-grandmother and seeing that photograph would change my life.

He showed us this photograph and he said, this is the oldest Gates on record.

Her name was Jane Gates she was a midwife and she was a slave.

MOORE: And you hadn't heard about her before this?

GATES: Never, I had not heard about her before.

"This is the oldest Gates on record," this is exactly what he said.

MOORE: Mm-hmm.

GATES: "I never want you to forget her name, and I never want you to forget her face."

And we looked at it, and this is like looking at a Martian.

She was so strange, she was dressed in her midwifery outfit, and the next day was July 3rd, 1960.

MOORE: Mm-hmm.

GATES: And that night I interviewed my mother and father about what only years later, I learned is called your family tree or your genealogy.

And, um, that was it, I was in it hook, line, and sinker.

And I never lost the fascination with my own family tree, never.

Perhaps ironically, the woman who sparked this fascination also harbored my family's biggest secret.

Growing up, I was told that Jane had five children, and that they all had the same father, but that Jane never told anyone his name.

My family spent years trying to identify this man, speculating wildly before finally settling on one likely candidate, a wealthy White landowner named Samuel Dunlap Brady.

Try, as we might, however, none of us could find records to confirm this story.

And CeCe proved it wrong.

She built a genetic network using DNA from my oldest relatives and discovered that Jane's youngest child, my great-grandfather Edward, was fathered by a man named Charles Wesley Kelley, a White farmer who would be killed by lightning when he was roughly 35 years old.

I had to confess this revelation did not exactly excite me.

I'd pictured my long-lost ancestor quite differently.

(laughing).

"Death By Lightning.

During the storm on Friday morning last, Charles W. Kelley was instantly killed by lightning.

He was in the act of closing a window at the time, and held in his hand a piece of iron or steel, which had been used to hold the sash up the lightning, struck him on the neck and passed out the toe of his boot."

This is my, this is my, you sure this is my ancestor?

This guy is stupid.

MOORE: I'm positive.

GATES: He's not the brightest star in the firmament, you know what I mean?

Wow.

You know, I'm thinking this guy is gonna be, you know, descended from one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence or something, you know?

He was a General in the American Revolution, something.

But here's this guy who just gets killed by lightning.

I mean this, I'm sorry for my great-great, and now I'm wrapping, you know, even as we're talking... MOORE: Mm-hmm.

GATES: I'm embracing Charles W. Kelley.

MOORE: I'm so glad.

GATES: And I'm sorry he was killed by lightning.

But it's not what I expected.

Setting my expectations aside... MOORE: Please turn the page.

GATES: CeCe now began to piece together the details of my ancestors' life.

Wow.

Records show that Charles Wesley Kelley was born around 1824 in Allegany County, Maryland.

And that he married a woman named Ellen Everstein when he was roughly 28 years old.

There were, of course, no records at all regarding the nature of the relationship between Charles and my enslaved great-great-grandmother Jane.

But based on his age, CeCe believed it was unlikely that Charles could have fathered all five of Jane's children.

What's more, CeCe thought it was possible that Charles never even met my great-grandfather, Edward, because Charles appears to have moved to Illinois before Edward was born.

Cause and effect.

Maybe he was run outta town.

MOORE: Maybe, or maybe he just didn't know.

GATES: Yeah, maybe he didn't know.

Maybe it's just a casual... MOORE: Maybe.

GATES: We like, we don't know.

MOORE: We don't know.

GATES: Hmm.

MOORE: That's one thing I guess we'll never know.

GATES: Never know.

Well, I hope there was some feeling involved.

But what's interesting is that Jane, according to my father, and the source of this must have been his grandfather.

MOORE: Mm-hmm.

GATES: Told the five children that they all had the same father and that he was White.

That was it.

MOORE: Mm-hmm.

GATES: But it's the kind of thing that you would, um, say to protect your reputation.

MOORE: Mm-hmm.

GATES: You know, you want your children not to think that they have assorted fathers, that they're all related to each other.

MOORE: So how do you think your father would react to learning this, that you are Kelleys on that direct paternal line?

GATES: Oh, I think he, no question.

He would believe you.

Overwhelmingly.

MOORE: Would he be happy about it or not so happy?

GATES: Um, he would wonder about the Brady story.

MOORE: Mm-hmm.

GATES: But he would definitely, I mean, he loves science, this is scientifically, uh, accurate.

He would make jokes forever about "Death by Lightning."

(laughing).

No question about that.

But no, he would definitely accept this.

By this time, I too, of course, had accepted CeCe's news, and I soon realized that it carried a silver lining.

The fact that Charles is my second great-grandfather means that his ancestors are my ancestors.

And CeCe was able to introduce me to a host of them.

Starting in the 1850 census where she found Charles living in a very crowded household.

"Charles Kelley, age 26, farmer; Hannah Kelley."

Whoa.

"Age 46.

Jacob Stotler, age 50.

Amanda Kelley, 18.

Mary Kelley, 12 and Fanny, 10."

MOORE: So this is the 1850 census for Allegany County, Maryland, do you recognize any of their names?

GATES: Yes, Charles Kelley.

MOORE: Right.

GATES: And someone 20 years older named Hannah, I am guessing is his mother, which would make her my third great-grandmother.

MOORE: Right.

You're jumping way ahead.

You know how this goes.

GATES: That's cool.

MOORE: So as you know, the 1850 census doesn't spell out the relationships, but it seemed very likely that the 46-year-old woman named Hannah is Charles' mother, while the three women ages 10 to 18 were his sisters.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

MOORE: And DNA supports this conclusion.

GATES: Mm-hmm, that's great.

MOORE: So this means that you just met your great-great-great grandmother, a woman named Hannah.

GATES: That is so cool.

Now, that's great.

This is the first addition up the tree.

MOORE: Mm-hmm.

GATES: Uh-huh, that's great.

That's fabulous.

MOORE: Now there's someone else on that census that stands out Jacob Stotler age 50.

GATES: Yeah, who is this dude living on the farm in isolation with an unmarried woman?

MOORE: Any guesses?

GATES: Um, her brother.

MOORE: Mm-hmm, good guess.

GATES: I'm pretty good.

MOORE: Yeah.

GATES: Oh, that's great.

MOORE: So we believe that he was Hannah's older brother and let me show you why.

Please turn the page.

GATES: Pretty good, huh?

Pretty good.

MOORE: So this is a marriage record.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

MOORE: From 1822 in Allegany County, Maryland.

GATES: Wow, cool.

"James Kelley married Hannah Stotler."

MOORE: Mm-hmm.

GATES: Nice.

So I'm a Stotler too.

MOORE: You keep reading my script for me.

That's right.

GATES: That's great.

MOORE: You are a Kelley and a Stotler.

GATES: And a Stotler.

MOORE: Mm-hmm.

GATES: That's cool.

MOORE: Had you ever heard the Stotler name around Cumberland?

GATES: I've never heard of the Stotler name around anywhere.

As it turns out, the Stotlers have lived in and around Cumberland since the early 1800s.

And learning that I was part of this family would lead to a startling discovery.

In all our years of researching Jane, no one had ever been able to uncover even a single detail about her life in slavery.

But as our team combed through the documents that the Stotlers left behind, they found what had eluded generations of Gates', an estate record listing Jane as a piece of property.

Ohhh!

MOORE: Okay, hold on.

Let me introduce you to this record.

GATES: Okay.

MOORE: You're looking at a part of the estate file of Christian Stotler, your great-great-great-grandmother Hannah Stotler's brother.

So remember Hannah had the brother, Jacob, she also has a brother Christian.

He died just outside of Cumberland on March 4th, 1859, only seven months before the death of his nephew, your great-great-grandfather, Charles Wesley Kelley.

GATES: Wow, these are the, this is the guy who owned Jane and her children.

That's amazing.

MOORE: Mm-hmm.

GATES: That is amazing.

Mm, mm, mm.

"An inventory of the personal property of Christian Stotler, late of Allegany County deceased, Negro woman, Jane, 37 years old, $500.

Negro girl, Clara, 11, $800.

Negro girl, Alice, nine years, $750.

Negro boy Henry seven..." That's was the source, by the way, of all the Henrys in family, down to me.

"...$500 and Negro boy Edward, 18 months, $200."

I can't believe you found this.

It is so stunning.

I am just floored.

MOORE: Did you ever imagine you would see this?

GATES: No, never, mm-mm.

MOORE: You've asked a lot of your guests this in the past, but how does it feel to see their names with dollar values assigned?

GATES: Oh, it's just, uh, I have tears my eyes, you know, it's, uh, I can't believe it.

I, this is the most amazing discovery that, um, I could have.

This is more amazing even than the identity of, uh, uh, Edward's father, really.

MOORE: That's what led us to this.

We had to make that discovery to find this.

GATES: Oh, that's, it's amazing, I can't believe it.

I just can't believe it after all this looking, I just can't believe it.

Mm.

Wow.

That's amazing, that is astonishing.

This is just gonna floor everybody.

I'm floored.

Based on this record, it seems that Jane met Charles Kelley when she was enslaved by his uncle Christian Stotler.

We don't know if Christian had any knowledge of the relationship, but in March of 1859, he made out his will, in reading it, I realized that if he had familial feelings towards Jane and her children, they were decidedly mixed.

Well, he freed Jane, that's the good news.

Then I read the second half.

Okay, this is a good news, bad news document.

MOORE: Mm-hmm.

GATES: "I desire that my servant woman, Jane, be free after further servitude of three years..." So that would be 1862, the middle of what would become the Civil War.

"...because of her faithful service to my family, however, I desire that my servant boys, Henry and Edward sons of Jane, my servant woman, be sold at private sale to good masters in the county or state and not be allowed to be sold out of state."

Hmm, boy, that's cold.

He, you know, he was freeing the mother, but keeping her sons in bondage.

MOORE: Though, he did say "They couldn't be sold out of state."

GATES: Yeah, but Maryland's got a whole lot of state.

MOORE: Yeah.

GATES: You know, you could be sold all the way down to the Eastern Shore where Frederick Douglass was from all the way from up here in western Maryland in the mountains.

That's cold and cruel.

MOORE: Yeah.

GATES: I wonder how Jane must have felt about that.

MOORE: What do you think?

GATES: It would've been devastating.

Jane would soon have to face this devastation head on.

Following Christian Stotler's death her family was torn apart.

Her two daughters were bequeathed to other members of the Stotler family.

Meanwhile, Jane and her young sons were sold.

With the boys "purchased for life" and Jane for a term of two years.

It was terrible to contemplate.

But the family historian in me could not help but be intrigued by something.

Hidden within the cold legal language of these transactions was a singular detail, "Additional list of the sales..." Oh.

"...On the personal property of Christian Stotler, late of Allegany County, deceased to wit, Merriam Stotler, and JH Stotler, two rifle guns, $16.

And to Samuel Brady, servant Jane, and her two children."

(laughter).

MOORE: There it is.

GATES: There it is.

That is amazing.

Boy, that shows you the power of oral tradition.

MOORE: Yeah, it wasn't out of nowhere.

GATES: No, it wasn't out of nowhere.

According to this record, Jane and her two boys, including my great-grandfather, Edward, were purchased by none other than Samuel Dunlap Brady.

Meaning that the man my family had long believed to be the father of Jane's children had actually been the last man who owned her.

They were close, they just didn't get it right.

MOORE: Isn't that the way it is with family stories, though?

There's usually a kernel of truth I have found, but it's often not quite right.

GATES: Yeah, this is astonishing.

This is, I could never have imagined that, um, any of this had been found.

Nothing.

I had now learned more about Jane than I'd ever dreamed possible.

She was no longer just my oldest Gates ancestor, suddenly she was a woman with a story, and that story had another beat to it.

We'd seen that Jane was part of Christian Stotler's estate when he passed away in 1859, and in the 1840 census, we saw that Christian owned three female slaves, likely Jane and two daughters.

But there was still a question in front of us.

MOORE: How did Christian Stotler come to own Jane Gates?

GATES: Mm-hmm.

MOORE: We found no indication he owned any enslaved people prior to 1840.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

MOORE: And indeed, we don't have a document that shows Christian acquiring any slaves, including your great-great-grandmother, Jane, at any time.

So we can't be certain, but as we dug deeper into the paper trail, we found a very interesting clue.

GATES: Okay.

MOORE: Please turn the page.

(laughing).

Now this is one of several obituaries of your great-great-grandmother, Jane, it was published on January 7th, 1888 in "The Cumberland Daily Times."

GATES: "Death of Aunt Jane Gates.

Last night at 11 o'clock, Aunt Jane Gates, colored, a family servant of the Stover's."

I've seen this before.

MOORE: Mm-hmm.

GATES: But I never could figure out who the Stovers were.

MOORE: Mm-hmm.

GATES: "Died in the 75th year of her age.

She's lived for a long time on Green Street where her death occurred."

So it's the Stovers.

MOORE: Yes.

GATES: That's the smoking pistol.

MOORE: That's right.

GATES: CeCe had indeed uncovered a smoking pistol.

Based on this obituary we now knew that Jane worked as a domestic servant for a family named Stover at the end of her life, which got our team wondering if Jane might've had a relationship with the Stover family earlier than that.

This led us back almost 50 years to a document I couldn't imagine even existed.

MOORE: This was published in a local Cumberland newspaper called "The Phoenix Civilian" on September 21st, 1839.

Would you please read the transcribed section?

GATES: "By virtue of deed of trust to me, executed by Solomon Stover and Harriet, his wife, I will sell at public sale at the residence of said Stover in Cumberland, one Negro woman and her two children, one an infant and the other about three years old.

Slaves for life."

Geez, boy that's cold, "Slaves for life."

MOORE: So Skip, we believe you're looking at an advertisement for the sale of your great-great-grandmother, Jane Gates, and her two young daughters.

Mm.

So they're owned by the Stovers.

MOORE: Mm-hmm.

GATES: And they're being sold.

MOORE: Right.

GATES: There you go.

"The Phoenix Civilian," never heard of it.

MOORE: What's it like to look at it and what did you think Jane would've been feeling?

GATES: You know, I've seen 1,000 bill of sales... MOORE: Mm-hmm.

GATES: But to know that that one Negro woman is my great-great-grandmother.

MOORE: Mm-hmm.

GATES: No, she must have been horrified.

MOORE: Yeah.

GATES: Yeah, I'll be thinking about this page for a long, long time.

CeCe told me that our researchers couldn't be certain, but they believe this represents the moment when Jane and two of her daughters were purchased by Christian Stotler.

What's more, it appears that one of the daughters was named Maria and that her very existence had been lost within my family's story.

Maria, who is Maria?

We never heard of her.

MOORE: We never had.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

MOORE: So it looks like Jane has six.

GATES: Jane had another child.

MOORE: Right, six children.

GATES: Yeah, amazing, okay.

MOORE: So remember Christian Stotler owned three enslaved females by the time the 1840 census was recorded.

GATES: Right.

MOORE: So this suggests that one was Jane, one was Maria.

GATES: Maria, who is a ghost, mm-hmm.

MOORE: And we searched high and low to try to find more information on Maria, and unfortunately we came up empty with her.

GATES: Okay.

MOORE: But we believe if she was living or if she had children or grandchildren, Jane would've mentioned them in her will.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

MOORE: Like she did her other children.

GATES: Right and she didn't, okay.

MOORE: So she may have died early.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

MOORE: Or she could have been sold away.

GATES: Mm-hmm, she could have been.

MOORE: We don't know.

GATES: Right.

MOORE: Would you please turn the page?

GATES: Alright.

MOORE: That's it, we're starting and ending.

GATES: That's great.

Hey grandma.

(laughs).

I know a lot more about you than I did four hours ago, I'll tell you that.

Wow, how fascinating.

MOORE: So what's it like looking at her now knowing all of this?

GATES: Well, I see a lot of pain in those eyes.

Hmmm.

And now I know why.

MOORE: Mm-hmm.

Did you see the pain before?

GATES: Mm-mm.

MOORE: Hmm.

GATES: No, no, not, not in the same way, no.

She just looked fierce.

MOORE: That's my impression of her.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

MOORE: Fierce, perfect word.

GATES: Yeah, I'm overwhelmed really.

It's deeply emotional too.

Yeah.

We'd already identified Laurence Fishburne's biological father solving a mystery that had haunted him for decades.

Now we turn to Laurence's father's ancestors, men and women whose lives Laurence had never even contemplated before.

As it turns out, one of them has an incredible story.

It begins with the 1870 census for Ohio, where we found Laurence's great-great-grandfather, a man named Paul Sandridge.

FISHBURNE: "Inhabitants in Jefferson Township in the county of Montgomery, state of Ohio.

Paul Sandridge, age 28, Black, occupation, farmer, place of birth, Virginia."

GATES: According to this census, your great-great-grandfather, Paul was born around 1842, which is 19 years before the outbreak of the Civil War... FISHBURNE: Mm-hmm.

GATES: ...In Virginia, so you know what that means?

FISHBURNE: Yes.

GATES: About his status.

FISHBURNE: He was enslaved.

GATES: He was enslaved.

FISHBURNE: Mm-hmm.

GATES: Have you given much thought to your, you know, you saw "Roots," right, we all did, to your ancestors who may have been enslaved?

FISHBURNE: All the time.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

FISHBURNE: All my life, I think... GATES: Mm-hmm.

FISHBURNE: Without knowing who they were or what they might have endured.

GATES: Right.

FISHBURNE: I've always known and really had a connection to that experience.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

FISHBURNE: Um, I've thought about it.

I've considered it, and I have used it as fuel to, uh, to make the most of my life.

GATES: We now set out to learn whatever we could about how Laurence's ancestors experienced slavery.

And immediately we faced a question, if Paul was born in Virginia, how did he end up in Ohio, roughly 300 miles away?

Searching for an answer we eventually focused on Paul's mother, a woman named Lucy Carpenter.

This led us to the archives of Amherst County, Virginia, where we found the estate records of a slave owner named Eaton Carpenter.

They suggest that Eaton shaped the fate of Laurence's family.

FISHBURNE: "I, Eaton Carpenter do make this to be my last will and testament.

It is my will and desire that all my slaves that I am possessed of at the time of my death be emancipated and set free.

It is my will and desire that all my estate, both land and perishable property, other than the slaves be sold by my executor upon such terms and in such manner as he shall think best, and the proceeds of the sales thereof be applied to the removal and settlement of the slaves to some of the free states.

The money arising from the proceeds of the sales of my land and perishable property shall be divided equally amongst them all to buy lands, to settle them upon."

Wow, that's amazing.

That's amazing.

GATES: So what do you make of this guy, old Eaton Carpenter?

FISHBURNE: Old Eaton.

Well, it makes me wonder what his relationship was to these people.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

FISHBURNE: That's what, that's the question.

GATES: Yeah, and it makes you think... FISHBURNE: He loved them... GATES: Mm-hmm.

FISHBURNE: ...He cared for them, yeah.

And was probably related to some of them.

GATES: I think those are reasonable assumptions.

FISHBURNE: Mm-hmm.

GATES: We believe that Eaton Carpenter was likely Paul's great-uncle, but he may have been his grandfather, or simply a right-minded man who wanted to free his slaves.

We can't be certain.

What we do know is that in the wake of Eaton's death, Paul and his mother and siblings journeyed north to Ohio, a free state where they took up farming.

We also know that Paul would do more with his life than farm.

In April of 1861, when he was about 20 years old, the Civil War erupted.

Roughly 19 months later with the outcome still very much in doubt the union finally began recruiting African Americans into the Army.

And Laurence's ancestor heeded the call.

FISHBURNE: "27 USCT, Paul Sandridge.

Private Company C. Where enlisted, Portsmouth.

When, mustered in, January 19th, 1864.

Where mustered in, Columbus.

GATES: Your great-great-grandfather enlisted in the Union Army.

FISHBURNE: And fought.

GATES: And fought.

FISHBURNE: God bless you.

GATES: What's it like to know that?

FISHBURNE: That's fantastic.

GATES: 180,000 Black men joined the United States Colored Troops to fight for the freedom of all their unfree brothers and sisters.

FISHBURNE: Right, my great-grandfather was one of them.

GATES: That's right.

FISHBURNE: Wow.

GATES: How about that?

FISHBURNE: That's amazing, that's really amazing.

GATES: Paul would quickly be forced to prove his worth as a soldier.

Just months after he enlisted, his regiment was sent south to join what became known as the Petersburg Campaign, a sprawling series of battles fought across southern Virginia.

The campaign lasted for almost a year and caused more than 70,000 casualties.

It was some of the most brutal combat of the entire war.

FISHBURNE: Oh my goodness.

GATES: So, Laurence, I want you to think about something, Paul's military service took it back to Virginia where he had been enslaved.

FISHBURNE: Where he'd been enslaved?

(laughing).

GATES: How about that?

FISHBURNE: It's fantastic.

GATES: The state in which he was born and enslaved until he was about 11 years old.

FISHBURNE: Oh man.

GATES: Yeah, what do you think that was like for him?

FISHBURNE: He had skin in the game.

GATES: Yeah.

FISHBURNE: He was... GATES: And he's old enough to remember if he's 11.

FISHBURNE: Yes, if he was 11, he remembers.

GATES: Yeah.

FISHBURNE: Yeah.

So he was ready to give his life.

GATES: Yeah.

FISHBURNE: He was ready to stand up and take one and give one, yeah.

GATES: Yeah, that took a nobility of soul.

FISHBURNE: That's right, and, and you know, real self-sacrifice, like real act of service.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

FISHBURNE: You know?

That's beautiful.

GATES: It is.

FISHBURNE: That's really beautiful, yeah.

GATES: Paul would pay a heavy price for his convictions.

On October 27th, 1864, he was shot through the ankle during a battle with Confederate troops.

Four days later, he found himself in a hospital in Alexandria, Virginia.

He'd remain there for months, likely in inconsiderable pain.

But suffering did not dim Paul's spirit.

To the contrary, we found his signature on a remarkable document, a petition protesting the way the Union was treating Black soldiers.

Would you please read that transcribed section?

FISHBURNE: "We, the undersigned convalescence of The Overture Hospital, learned that the government has purchased ground to be exclusively for the burial of soldiers of the United States Army, and has also purchased ground to be used for the burial of contrabands or freed men."

GATES: Mm-hmm.

FISHBURNE: "We are not contrabands, but soldiers of the U.S. Army fighting side by side with the White soldiers as American citizens.

We are now sharing equally the dangers and hardships in this mighty contest and should share the same privileges and rights of burial.

We ask that our bodies may find a resting place in the ground designated for the burial of the brave defenders of our country's flag.

Paul Sandridge."

GATES: What's it like to see that?

FISHBURNE: It's magnificent.

It's absolutely magnificent and very American.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

FISHBURNE: Deeply American.

GATES: It is.

FISHBURNE: Yeah, that's what it is.

GATES: He put his life on the line.

FISHBURNE: Yes.

GATES: He went back to where he was enslaved.

FISHBURNE: That's right.

GATES: He didn't have to do that.

FISHBURNE: Didn't have to do that.

GATES: Volunteered to do that.

FISHBURNE: That's right.

GATES: And then when he susses out the fact that there's this racial discrimination... FISHBURNE: He's like, we're not... GATES: ...Takes a stand.

FISHBURNE: ...Not standing for that.

GATES: And that's your great-great-grandfather.

FISHBURNE: That's incredible, that's incredible.

GATES: This story has a happy ending.

Paul's petition made its way to the Quartermaster General of the United States Army and led to real change as Black soldiers began to be buried alongside their White comrades.

What's more, Paul survived his wound and returned to Ohio where he married and started a family.

He would live to be 80 years old before passing away on May 27th, 1921.

And his pension records suggests he worked almost right up until the end of his life.

FISHBURNE: Until he was 80.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

FISHBURNE: He kept trying... GATES: Yeah.

FISHBURNE: ...To be a man and, and be whole.

GATES: And to be productive.

FISHBURNE: Right and useful.

GATES: Yeah.

FISHBURNE: Wow, I love it.

With a, with a bum leg, right?

GATES: Yeah.

FISHBURNE: With a bum ankle.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

FISHBURNE: Amazing.

GATES: Believed in himself.

FISHBURNE: Mm.

GATES: Believed in the future.

FISHBURNE: Mm.

GATES: He would not capitulate... FISHBURNE: Right.

GATES: ...To adversity.

FISHBURNE: At 80 in 1921.

GATES: Yeah.

FISHBURNE: 102 years ago.

GATES: Yep.

FISHBURNE: Damn, that's great, that's great.

Hmm, okay.

GATES: Please turn the page.

FISHBURNE: Hello.

GATES: Look on your right.

FISHBURNE: No?

You found his headstone?

GATES: Yes.

FISHBURNE: What?

GATES: That is your great-great-grandfather's headstone.

FISHBURNE: In Ohio or in Virginia?

GATES: Mm-hmm, in Dayton.

FISHBURNE: Oh my gosh.

That's amazing.

GATES: He's buried in the lower Miami Cemetery in Dayton.

FISHBURNE: In Dayton, Ohio.

GATES: Ohio.

FISHBURNE: Interesting.

I'll have to go visit.

GATES: And on the left.

FISHBURNE: Mm-hmm.

GATES: I don't know if you've ever been to the African American Civil War Memorial in D.C. FISHBURNE: I have not.

GATES: On the left is your great-great-grandfather Paul Sandridge's name... FISHBURNE: I see him right there in the center, look at that.

GATES: ...Etched into the wall.

FISHBURNE: That's crazy.

GATES: Isn't that cool?

FISHBURNE: That's, wow.

That's awesome.

GATES: What's it been like to learn Paul's story?

FISHBURNE: It's just, it's, it's pretty special.

It's very special.

I didn't expect any of this at all.

I know about these stories, I've heard these stories, but I, I didn't think that my, I would be connected to one of them.

GATES: We didn't either.

FISHBURNE: I didn't think that you know... GATES: We were just trying to find... FISHBURNE: Yeah, we was trying to find Fishburne, right?

GATES: Yeah right.

(laughing).

We tryin' to find the boy's daddy.

(laughing).

The paper trail had now run out for Laurence and me.

That's yours.

FISHBURNE: Oh wow.

GATES: It was time for us to see our full family trees.

Wow.

MOORE: There you go.

GATES: Look at this baby.

FISHBURNE: Oh man.

GATES: This is your family tree brother.

Now filled with ancestors whose names we had long hoped to learn.

For each of us, it was a profound sight.

This is so deeply moving, I mean, stunningly powerful.

You're related to all these people, what's that mean to you?

FISHBURNE: It means everything, man.

It means everything.

It means I have a history where before, just when I walked in here today, I didn't.

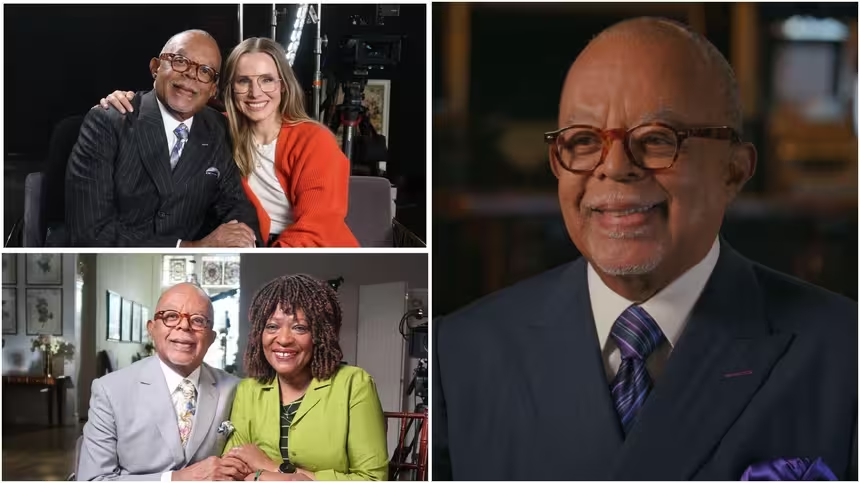

GATES: My time with Laurence had come to an end, but his journey was not yet over.

He was soon on his way to Los Angeles to meet two brand-new members of his family.

FISHBURNE: Oh my God.

GATES: His half-siblings, Lisa and William Bohannan, the younger children of his biological father.

LISA: This is when he was at his happiest.

WILLIAM: The whole, you know, thing with the records and DJing, that was his thing.

LISA: It was, we would wake up before Saturday morning cartoons to jazz playing in the house.

WILLIAM: Right, right, exactly.

Wow, handsome devil.

GATES: For all three it was a magical moment.

FISHBURNE: This is grandma?

LISA: This is Dad.

GATES: A chance to forge bonds.

FISHBURNE: See.

GATES: Share stories.

And celebrate the man who tied them together.

FISHBURNE: I love this.

LISA: Yeah.

FISHBURNE: I absolutely love this.

Hey.

LISA: Family.

(camera shuttering) GATES: Just like Laurence, I too had a magical moment awaiting me.

The day after my meeting with CeCe, I went to a family reunion.

Good afternoon, everyone.

And told everyone what I'd learned... ...Jane Gates, so the family story was passed down that we were Brady's.

We were Brady's, property of the Brady's, Samuel Dunlap Brady purchased Jane, Henry and Edward on April 28th, 1860.

That's where the myth of the Brady family came in.

Isn't that incredible?

So all you Gates', you can have your driver's license changed, we have a special fee for that, your birth certificates, your new surname is Kelley.

Isn't that amazing?

People were so close in the story...

The room was filled with my closest relatives, my older daughter and granddaughter, my brother, my nieces and nephews, and dozens of my beloved cousins.

Each of us, a direct descendant of one incredible woman.

So now we have a continuous paper trail for Jane Gates going back between 1830 and her death on the 6th of January, 1888.

We know that she was owned by three different White families, started with the Stovers, then the Stotlers, and then the Bradys between 1830 at least, and her freedom in 1862.

And that is the wizardry of CeCe Moore.

Please give it up.

It's hard even to be, begin to imagine what Jane would've thought of all of this.

But my guess is that she would've been proud to see that her legacy had proved to be so large and so joyous.

That's the end for now of my search for Laurence Fishburne's family and my own.

Please join me next time when we unlock the secrets of the past for new guests on another episode of "Finding Your Roots."

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S11 Ep10 | 30s | Family mysteries are solved for actor Laurence Fishburne & scholar Henry Louis Gates, Jr. (30s)

Laurence Learns About His Great-Great-Great-Grandmother

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S11 Ep10 | 4m 12s | Laurence discovers the identity of his great-great-great-grandmother. (4m 12s)

Skip Discovers His Great-Great-Grandfather

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S11 Ep10 | 4m 14s | Skip discusses Jane Gates, his oldest known ancestor up until now. (4m 14s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- History

Great Migrations: A People on The Move

Great Migrations explores how a series of Black migrations have shaped America.

Support for PBS provided by: