Flannery

3/23/2021 | 1h 23m 23sVideo has Closed Captions

Explore the world of a literary icon whose fiction was unlike anything published before.

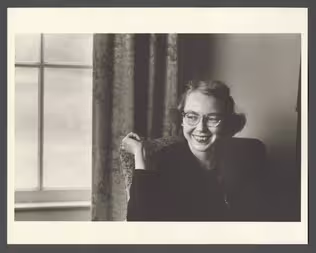

Explore the life of Flannery O’Connor whose provocative fiction was unlike anything published before. Featuring never-before-seen archival footage, newly discovered journals and interviews with Mary Karr, Tommy Lee Jones, Hilton Als and more.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Support for American Masters is provided by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, AARP, Rosalind P. Walter Foundation, Judith and Burton Resnick, Blanche and Hayward Cirker Charitable Lead Annuity Trust, Koo...

Flannery

3/23/2021 | 1h 23m 23sVideo has Closed Captions

Explore the life of Flannery O’Connor whose provocative fiction was unlike anything published before. Featuring never-before-seen archival footage, newly discovered journals and interviews with Mary Karr, Tommy Lee Jones, Hilton Als and more.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch American Masters

American Masters is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

A front row seat to the creative process

How do today’s masters create their art? Each episode an artist reveals how they brought their creative work to life. Hear from artists across disciplines, like actor Joseph Gordon-Levitt, singer-songwriter Jewel, author Min Jin Lee, and more on our podcast "American Masters: Creative Spark."Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship♪♪ ♪♪ [ Birds squawking ] ♪♪ [ Animals lowing, bleating ] ♪♪ [ Clattering in distance ] ♪♪ [ Animal lowing ] ♪♪ [ Footsteps ] [ Zipper zips ] ♪♪ [ Door opens ] ♪♪ Breit: This program is an attempt to bring forward the most exciting new books we know of.

Such a book is a collection of short stories, "A Good Man Is Hard to Find."

One critic called her perhaps the most naturally gifted of the youngest generation of American novelists.

Here she is, Flannery O'Connor.

O'Connor: The grandmother didn't want to go to Florida.

She wanted to visit some of her connections in East Tennessee and she was seizing at every chance.

Chang: To change Bailey's mind.

Bailey was the son she lived with, her only boy.

O'Connor: "Now look here, Bailey," she said, "see here, read this.

Here this fellow that calls himself The Misfit is aloose from the federal pen and headed toward Florida."

[ Cat meows ] O'Brien: I love Southern writing.

I particularly loved Flannery O'Connor.

You think it's this bitter, old alcoholic who's writing these really funny dark stories, and then you find out she's a woman and that she's devoutly religious.

♪♪ Als: How is she going to find the stories that she knows she needs to tell, and how is she going to tell them?

[ Typewriter clacking ] Walker: She was able to go straight to the craziness without always trying to make the craziness black or the craziness white.

She just saw the mystery of the craziness.

♪♪ McDermott: Flannery O'Connor's life in some ways could have come out of a Flannery O'Connor story.

It was the illness I think that made her the writer that she is.

[ Ducks quacking ] Gordon: Flannery O'Connor is one of the maybe five or six writers in the history of the world who is least afraid to look at the darkness.

Jones: You have a wolf dressed up as a grandma.

Something's going to happen.

♪♪ ♪♪ [ Birds chirping, squawking ] ♪♪ [ Rooster crowing ] ♪♪ ♪♪ [ Typewriter clacking ] ♪♪ ♪♪ Steenburgen: Whenever I'm asked why Southern writers particularly have a pension for writing about freaks, I say it is because we are still able to recognize one.

♪♪ Man: Alright, ladies and gentlemen.

Step right up.

Here they are, fresh roasted peanuts.

Peanuts, popcorn, candy apples... [ Speaking indistinctly ] [ Vehicle horn ah-oogahs ] Abbot: In a small town, you can lie, you can steal, you can commit adultery, you can even murder somebody, but you can't not go to church.

[ Laughs ] [ Bell tolling ] ♪♪ [ Indistinct conversations ] [ Cutlery clinking ] [ Children laughing ] ♪♪ [ Dog barking ] [ Marching band drums playing ] Gooch: Mary Flannery O'Connor was born in Savannah, Georgia, into an Irish Catholic immigrant community She was in a largely Protestant town, but a very cosmopolitan town.

♪♪ Jones: She's far more American than she is Irish, and she's far more Southern than she is American.

♪♪ Sally: She was shy.

But she was not timid.

And she was considered a little uppity by the nuns in the parochial school she attended in Savannah.

♪♪ She had a rather fortunate childhood, a very fortunate childhood.

Her father adored her, and so did her mother, of course.

But they saw her in quite different ways.

She was able to see herself in different ways.

Steenburgen: When I was 5, I had an experience that marked me for life.

Pathe News sent a photographer from New York to Savannah to take a picture of a chicken of mine.

Male reporter: Here's Mary O'Connor of Savannah, Georgia, holding the only chicken in the world that actually walks backwards.

When she advances, she retreats.

To go forward, she goes back, and when she arrives, she's really leaving.

Gooch: You'd see her at age 5 calm and in charge.

I mean, there's something about her that's bewitching at that age.

She came back to this incident often.

She began to raise these special birds.

[ Chickens clucking ] She would joke about how she would then begin to raise one-eyed chickens to try to lure the film company to come back to town, but they never did.

[ Birds squawking ] [ Typewriter clacking ] ♪♪ Wood: I would say her signature story is "A Temple of the Holy Ghost," because it envisions this young girl who is clearly a version of Flannery O'Connor.

[ Cheers and applause ] O'Donnell: The story is very provocative in exactly the way that O'Connor's stories usually are.

[ Laughter ] For one thing, she incorporates what she calls a freak -- a person who is not like everybody else, a person who is radically non-conformist.

[ Girls singing in Latin ] Two visiting cousins go to see, at the fair, this intersex person.

Als: The two girls are singing in Latin.

They're Catholic girls.

They go to Catholic school.

The boys in the town, they call it Jew singing.

[ Girls singing in Latin ] ♪♪ O'Donnell: The child in the story is too young to go, so she doesn't actually get to see the person, but she is fascinated by this idea of someone who can be both male and female, yet neither male nor female.

[ Laughter ] Steenburgen: He could strike you thisaway.

Amen.

Amen.

But he has not.

Amen.

O'Donnell: This child's faith life is in some ways a version of Flannery's own faith life in which she has doubts.

She decides, "I could never be a saint," but she could be a martyr if they killed her quick.

Then she thinks about the ways in which she would be willing to die -- you know, boiled in oil, maybe, probably being torn apart by animals.

[ Lions growling ] [ Girl screaming ] Gordon: If you went to mass, you heard those prayers over and over again.

You were encouraged to pray silently, even oddly to contemplate, at a very young age Steenburgen: Her mind began to get quiet and then empty.

But when the priest raised the monstrance with the host shining ivory colored in the center of it, she was thinking of the tent at the fair that had the freak in it.

You are God's temple, don't you know.

O'Donnell: The child puts together this mystery of a human being and herself and recognizes her brokenness in his brokenness.

Rodriguez: What's happening here is something so remarkable that the profane meets with the sacred, and it's within that comic meeting that the stories operate.

[ Cheers and applause ] This is the way Flannery O'Connor works.

You either get it or you don't, and if you don't, then don't go to the carnival.

♪♪ Steenburgen: God's spirit has a dwelling in you, don't you know.

Amen.

[ Bird chirping ] Breit: What does a writer try to do in a short story?

Or what does a writer try to do in a novel?

What is the secret of writing?

O'Connor: Well, I think that a serious fiction writer describes an action only in order to reveal a mystery.

Of course, he may be revealing the mystery to himself at the same time that he's revealing it to everyone else.

And he may not even succeed in revealing it to himself, but I think he must sense its presence.

♪♪ Sessions: Her father, he was a man like many people I know of that generation.

He simply couldn't make it.

The old economies in the South had just collapsed.

Essentially, they were Faulkner's generation.

The cities were where things were happening.

♪♪ O'Donnell: They moved from Savannah to Atlanta because that's where he could get work.

Flannery did not like it there, nor did her mother.

Regina, her mother, and Flannery relocated to Milledgeville to the Cline family mansion.

Edward would come home and visit them on weekends, but they were used to living without him for five days a week.

Brown: Regina had grown up in rather genteel circumstances in Milledgeville.

Her family, the Cline family, were a very prominent family in the town, much respected by other people there, one of the very few Roman Catholic families.

[ Indistinct conversations echoing ] Sally: She was used to people getting sick, dying, strokes.

She always had a strong sense of mortality.

♪♪ Sessions: The O'Connors had no money.

The money came from Aunt Mary, who had had inherited money and had land, and these were not integrationists, I can tell you.

♪♪ Sally: Flannery's writing is all about original sin, about the human condition.

What a mess we are.

Sessions: The time that Flannery lived, the three K's were always Coons, Kikes, and Catholics -- that is, African-Americans, Jews, and Catholics.

Sally: Catholics were very suspect.

So there was a kind of siege mentality by Catholics.

But this was good for Flannery, because it meant that she didn't take for granted widespread approval.

She ignored the disapproval of her religion.

She ignored the disapproval of her fiction.

♪♪ Sessions: If you look at her in that direction, you don't get this kind of romantic artist.

You get someone who's writing out of a specific time, a specific code, and a specific set of manners.

And the interesting thing is, what she found in all those manners was mystery.

[ Children speaking indistinctly ] ♪♪ ♪♪ Sally: Flannery's father was the one who encouraged her literary ambitions.

Her mother was interested in improving her -- corrective shoes, braces, everything.

The father, on the other hand, liked her as she was.

Gooch: Ed O'Connor is a sensitive, charismatic man who really went for her work and her cartoons and her writing and her creativity.

Her father would carry around with him every day these little drawings and things that she made and show them to people.

He was very proud of them.

[ Person snoring ] Sessions: Her drawings are marvelous, these sharp faces.

Woman: You old wart hog.

Sessions: Flannery would write to her father little letters in the house, and they'd be under the napkins at breakfast.

And then he would write her little letters back.

Sally: He had wanted to write himself, as she noted one of her letters.

♪♪ She was 12 when he fell ill, 15 when she lost him.

♪♪ And he died from lupus.

They had no treatment for lupus.

♪♪ ♪♪ O'Donnell: The death of Edward O'Connor, no doubt, was a major turning point in her life.

Up until that time, she had had a reasonably happy childhood.

She was much loved.

She was an only child.

She had the full attention of both of her parents, and a loss of that suddenly was a huge void for her.

♪♪ Sally: "I suppose what I mean about my father is that he would've written well if he could have.

Needing people badly and not getting them may turn you in a creative direction.

He needed the people, I guess, and got them or rather wanted them and got them.

I wanted them and didn't."

♪♪ [ Typewriter clacking ] Steenburgen: Anybody who's survived his childhood has enough information about life to last him the rest of his days.

Man #2: Ready on the firing line.

[ Whistles ] ♪♪ ♪♪ Gooch: Flannery O'Connor started doing her writing during World War II when she was a student in Milledgeville at the Georgia State College for Women.

♪♪ It was actually an interesting, important moment.

She was in a women's college.

Most of the men were away fighting the war.

Gentry: The women professors here were encouraging the female students to think about the various things that they could do with their lives, and Flannery picked up on hints about how the world was changing.

♪♪ Sally: She was very gifted as a caricaturist, and you could see that from the work.

Gooch: She does cartoons which were then published in the student newspaper and in the yearbook about life on campus, but they're not happy, prom, sorority visions of life on campus.

[ Typewriter clacking ] ♪♪ Steenburgen: Oh, don't worry about not getting on the Dean's list.

It's no fun going to the picture show at night anyway.

[ Man speaking indistinctly ] Gooch: When the Waves are on campus, who were Navy women, she makes fun of them as if they're an occupying force taking over the campus.

This early sensibility is both sarcastic, empathetic, and funny and weird all at once.

[ Bow string snaps, twangs ] Sally: She thought she wanted to be a serious writer who would support herself by cartoons.

Gooch: She actually has great ambitions for her cartoons.

She would send them to the New Yorker when James Thurber was the great New Yorker cartoonist.

♪♪ Sally: She kept an orderly journal, which she called "Higher Mathematics."

What she did was very interesting, because we learned so much about her, how she felt about her shyness.

She said, "Sometimes I think I would give it all up for just a little social ease."

Steenburgen: One new quarter of college begun.

I achieved a nice success in English 360 by making a rather humorous remark and then not laughing at it while the others did.

This is the sort of me I strive to build up -- the Cool, Sophisticated, Clever Wit.

The inarticulate, confused blunderer overwhelms the CSCW most of the time.

[ Indistinct conversations ] ♪♪ Gentry: She would never call herself a feminist, but she saw what her classmates were doing.

She could leave Mother.

She could become a political cartoonist and have a career.

Steenburgen: Today, I envision myself as a cartoonist block printer of national repute.

I'll make $400,000 before graduating from college and, with it in tow, prepare for the leisurely life of a lethargic scholar and traveler.

♪♪ Gentry: She knew that was going outside the usual prescribed roles for a woman.

[ Indistinct conversations ] Gooch: In these early cartoons, you can almost see, weirdly, O'Connor's aesthetic intact.

♪♪ Steenburgen: Today I'm devoted to realism.

I will become a realist.

I will take note of the things around me accurately.

I wonder if some of these mental, emotional, social things that are happening to me and the people around me could crystallize into a novel.

I must write a novel.

♪♪ ♪♪ [ Typewriter clacking ] [ Typewriter dings, clicks ] Brown: The writing program there was very high powered.

I suppose it was the most famous in the country, and Flannery found herself you know, in a literary hotbed.

Gordon: There is no Flannery O'Connor without leaving Georgia.

She's around people who get her maybe for the first time.

She gets exposed to literature, I think in a way that she never had been before.

I think maybe at Iowa is the first time she didn't feel like the absolutely smartest person in the room.

Gooch: Paul Engle had just started a very important writers program, attracting all these soldiers coming back from World War II who wanted to write the great American novel.

♪♪ Southern fiction was the hot fiction, and William Faulkner was the great modernist writer.

The men in the class were making fun of her for her writing and also for her Southern accent.

O'Donnell: Workshops can be pretty brutal.

[ Chuckles ] Chang: She was very shy.

People who were there thought maybe she wouldn't be much of a writer, but the professors at the workshop instantly knew that she was talented.

Sally: Paul Engle recognized her talent at once and immediately began to make a reading list for her.

And she drank it in.

She read Henry James.

She read the Russians.

Dostoevsky.

Chang: At Iowa, we've had a great interest in writing about racial dynamics.

And I think that that's clear in Flannery O'Connor's work.

If you can immerse yourself into a piece of work that you deeply love, it will change you from the inside, and you will then be able to write differently.

O'Donnell: This is the first page of "The Geranium."

It's the first story that O'Connor wrote here.

Dudley, the old man who is at the center of the story living in New York City, is horrified to realize that a black man has moved into the apartment across the hallway.

Dudley tries to deal with terrible homesickness.

He becomes very attached to a geranium that one of the neighbors puts outside of their window.

There's a scene in the story where Dudley stumbles on the stairs, and who picks him up and helps him back to his apartment but this young black man who has moved across the hall Gooch: She was trying to work out, almost sweetly and innocently, dealing with race in her work and also in terms of Catholicism.

[ Pigeon cooing ] ♪♪ Gentry: If you take a look at the prayer journal, her transcribed prayers that she was copying out while she was in graduate school, she was spending a surprising amount of time talking to God about the subconscious and the unconscious.

Gooch: Instead of going to the tavern every night with the students, she went every morning to church.

♪♪ Steenburgen: Oh dear God, I want to write a novel, a good novel.

I want to do this for a good feeling and for a bad one.

The bad one is uppermost.

The psychologists say it is a natural one.

♪♪ Karr: She's completely humble in her enterprise.

You see it in her prayer journal.

She's not trying to put herself forward as the storyteller, as the wise woman, as the clever girl.

"I must write down that I am to be an artist, not in the sense of aesthetic frippery, but in the sense of aesthetic craftsmanship.

Otherwise I will feel my loneliness continually, like this today.

I do not want to be lonely all my life, but people only make us lonelier by reminding us of God."

♪♪ It's unbelievable.

McDermott: It's a tremendous and astonishing, in some way, unmovable faith that I don't think contemporary writers of any kind could sustain.

Als: I think Flannery O'Connor's travels, I think they're vital.

You don't know what home is until you leave it.

♪♪ Steenburgen: Dear God, I cannot love thee the way I want to.

You are the slim crescent of a moon that I see, and myself is the earth's shadow that keeps me from seeing all the moon.

♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ [ Indistinct conversations ] ♪♪ [ Typewriter clacking ] ♪♪ Gooch: After being at the writers workshop for three years, she was admitted to Yaddo, a program in Saratoga Springs where writers famously went and were able to devote themselves to their writing.

There was a kind of Southern renaissance Truman Capote had in there, Carson McCullers.

♪♪ She changes from Mary Flannery to Flannery O'Connor in this period, partly to escape the Southern double name and also because as a writer in that period, being a woman writer was already difficult.

When she sent out some of her first stories to magazines, she got at least one rejection letter back addressed to Mr. Flannery O'Connor.

[ Indistinct conversations ] Most of the tales of Yaddo are tales of Carson McCullers being drunk and everyone being drunk, apparently.

Steenburgen: This is not sin but experience, and if you do not sleep with the opposite sex, then it is assumed you sleep with your own.

Gordon: Her time at Yaddo was intense and complicated.

Lowell is there.

Elizabeth Hardwick's there.

And she has a big crush on Lowell in a way that's heartbreaking.

He was very sexy, very good looking, but he was with Elizabeth Hardwick, who was kind of a glamour girl, also a Southern girl.

Steenburgen: You ask about Cal Lowell.

I feel almost too much about him to be able to get to the heart of it.

He is a kind of grief to me.

Gooch: In his late 20s, he already won a Pulitzer Prize.

Lowell was haunted by Christianity.

He was almost projecting onto O'Connor a kind of Catholic sainthood Steenburgen: I watched him that winter come back into the church.

I had nothing to do with it, but of course it was a great joy to me.

Gooch: At the same time that she was writing "Wise Blood" about Christ's haunted character who's also falling apart all the time.

[ Typewriter clacking ] Gordon: He's crazy.

He's bipolar.

He got her involved in this anticommunist witch hunt.

[ Men laughing, speaking indistinctly ] Gooch: Flannery was walking through this kind of political minefield that was going on in America at the time.

Lowell accused the director of harboring a communist.

He had O'Connor testifying.

Congressman: The communist party's a minority, and a dangerous minority.

I believe that the entire nation should be alerted to its menace today.

Gooch: Communism was atheistic and was against her religion.

Gordon: Not the most admirable moment of her life, but I think she would have done anything he asked her to do.

Steenburgen: We have been very upset at Yaddo lately, and all the guests are leaving in a group Tuesday.

The revolution.

I'll probably have to be in New York a month or so, and I'll be looking for a place to stay.

Oh, this has been very disruptive to the book, and it's changed my plans entirely, as I definitely won't be coming back to Yaddo.

♪♪ ♪♪ [ Engine starts ] ♪♪ [ Whistle blows, horn honks ] [ Crowd speaking indistinctly ] [ Bell tolling ] O'Connor: There were reasons that intensified the grotesque quality of some writing in these times.

I feel that the grotesque quality of my own work is intensified by the fact that I'm both a Southern and a Catholic writer.

[ Car horns honking ] ♪♪ Gooch: Lowell, helpfully, maybe guiltily, takes her to meet Robert Fitzgerald, translator and poet, and Sally Fitzgerald, who then become O'Connor's really closest friends and kind of second family for her.

Sally: One afternoon, the doorbell rang, and Cal was standing there with a shy young woman in corduroy slacks and navy pea coat.

Flannery had been living in a furnished room in someone's apartment up on the Upper West Side.

And she was pretty miserable.

So we said, "Well, why don't you come and live with us, be our boarder?"

McDermott: Underlying all that was the process of writing "Wise Blood," the struggle and the rewriting and the rewriting, as young as she was.

She was still in her early 20s, I guess.

Here's a big revelation.

[ Chuckles ] I think we all write somewhere in our notebooks, "Oh, this is no good."

You know?

I think you can see in her letters about working on "Wise Blood" and the process that she went through, her first publisher who didn't get it.

Giroux: Flannery said that, "The editor at Holt treats me like a dim-witted campfire girl."

Sally: He called her prematurely arrogant.

Gooch: And O'Connor, very young, I mean, completely stands up for herself and the possibility that this book will never be published and just says that, "I'm not writing this kind of novel."

Sally: Publishers never intimidated her.

Steenburgen: I am not writing a conventional novel, and I think that the quality of the novel I write will derive precisely from the peculiarity or the aloneness, if you will, of the experience I write from.

Giroux: She was very clear-eyed.

You know, there are people you take one look at, and you know that's a bum or that's a liar.

With her, it was, "That's an honest person."

I published every book she wrote.

Sally: One day she said, "You know, I think I'd better see a doctor, because I can't raise my arms to the typewriter."

I made the appointment with the doctor.

He said, "I suggest that when you go back to Milledgeville, you check into the hospital and have a complete physical examination."

♪♪ Louise: When Uncle Louis met her at the station in Atlanta, he said that she looked like she was 1,000 years old.

She was so sick.

Sally: Doctor Arthur Merrill in Atlanta realized that it was lupus, and it was advanced.

He told her mother, but her mother, knowing that the father had died of the same disease, thought that the shock would be too great for Flannery and decided not to tell her.

Mrs. O'Connor told us of this decision.

Of course, we honored it.

She lost her hair.

She was rather disfigured by the medicine.

It could be combated, although not cured, by cortisone.

This is the way she was able to live as long as she did.

Flannery continued to talk about her arthritis and the fact that she was looking forward to getting back to Connecticut.

Never did send for her books, never sent for her clothes.

Sessions: She never stopped writing.

She was a good stonemason, good artisan, so that way in everything.

Virgil wrote a line a day.

Flaubert wrote a paragraph a day, but they were craftsmen.

They weren't trying to save the world.

Steenburgen: In a sense, sickness is a place more instructive than a long trip to Europe.

It's a place where there's no company, where nobody can follow.

♪♪ [ Typewriter clacking ] ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ Motes: I'm a preacher.

Landlady: What church?

Motes: Church of Truth Without Christ.

Landlady: Protestant?

Or, or something foreign?

Motes: Oh, no, ma'am.

It's protestant.

O'Donnell: People did not really understand "Wise Blood" when it first came out.

They all mistook her first book as being the work of a nihilist.

Motes: There ain't but one thing that I want you to understand, and that's that I don't believe in anything.

Driver: Nothing at all?

Motes: Nothing.

O'Donnell: Primarily because Hazel Motes is one of O'Connor's characters who is running away from God but is hounded by God.

Asa: Some preacher's left his mark on you.

O'Donnell: Always doing the most outrageous things -- Going to a whorehouse, preaching the church of Christ without Christ.

Motes: The church without Christ don't have a Jesus.

O'Donnell: Murdering people in the street.

And yet, every time he turns around, there's that ragged figure that's following him, that's following him.

Enoch: Now we got shut of them, why don't we go someplace and have us some fun?

O'Donnell: He can't estrange God, and there's no way you could ever entirely estrange yourself from God.

So O'Connor understands this.

This is her theology.

Motes: There's no peace for the redeemed.

If they was three crosses there, and Jesus Christ hung... Michael: When I went to do her first novel as a film, I, in a very calculated way, I chose a director who was an atheist, because I did not want some soppy, religious thing, and she would have hated it.

Motes: Where you come from is gone.

Where you thought you were going to, weren't never there.

Michael: But when she wrote the novel in my parents' house, my father was at the time translating the Oedipus Rex of Sophocles, which she had never read.

Landlady: What you gonna do with that, Mr. Motes?

Michael: She was so shocked by the Oedipus Rex that she reworked the entire novel to accommodate Hazel Motes' blinding himself, as Oedipus does.

Dourif: There is where the razor's edge of "Wise Blood" and Flannery O'Connor really are.

Landlady: Mr. Motes, what's that wire around you for?

Dourif: How can a person really be a saint?

What kind of a saint would that person be, she wondered?

Benedict: Now I remember on the last day, John, his hands over my shoulders, leaned in and said, "Ben, I think I've been had."

By the end, he realized, "I've told another story than the one I thought I was telling.

I've told Flannery O'Connor's story."

Dourif: Huston kind of looks down, and he looks up at everybody and looks around.

And he says, "Jesus wins."

[ Footsteps ] Man #3: Here you are, little lady.

And thank you, madam.

Thank you very much.

Alright, ladies and gentlemen.

Williams: ♪ Get right with God ♪ ♪ I would sleep on a bed of nails ♪ ♪ Till my back was torn and bleeding ♪ ♪ In the deep darkness of hell ♪ ♪ The Damascus of my meeting ♪ ♪ I want to get right with God ♪ ♪ Yes, you know ♪ Sally: It was admired.

It was very much admired, because its power was undeniable.

But critics didn't understand it.

Giroux: I'll tell you that the publishing point of view was, "This book is a flop."

It got bad reviews.

I was shocked at the stupidity of these reviews, the lack of perception or even the lack of having an open mind about it.

Steenburgen: The review in Time was terrible.

Nearly gave me apoplexy.

The one in the Atlanta Journal was so stupid, it was painful.

It was written, I understand, by the lady who writes about gardening.

They shouldn't have taken her away from the petunias.

♪♪ Frances: At the autograph party in Milledgeville, all the ladies came, and they were all excited about this new author in town.

They all walked away with her book, "Wise Blood," all autographed and everything.

And I think she was just kind of chuckling to herself as she saw them all leave the room, thinking, "Oh, wait till they find out.

Wait till they really see what it's all about."

♪♪ ♪♪ Louise: Bernard Cline, brother of Regina, put together three tracts of land which became Andalusia Farm.

In 1951, when Flannery became so ill, it was possible for them to move out here.

♪♪ Regina continued to run it as a dairy farm.

They both could live on the ground floor and not have to climb stairs to the second floor.

Gooch: She was confined on this farm, and she really found her material around her in that setting.

Sally: She realized that she didn't have to sit in New York and lose her ear for Southern speech, that she had it everywhere.

The farm women, the farm people, everything was grist for her mill.

[ Birds screeching ] O'Connor: Everything is getting terrible.

I remember the day you could go off and leave your screen door unlatched.

Not no more.

Sally: One day, Flannery and I had driven over to Milledgeville to do errands.

She said something again about her arthritis.

I said, "Flannery, you don't have arthritis.

You have lupus."

Her hand was shaking.

My knee was shaking on the clutch.

And we drove back up and down the road, and in a few minutes, she said, "Well, that's not good news.

But I can't thank you enough for telling me.

I thought I had lupus.

And I thought I was going crazy.

And I'd a lot rather be sick than crazy."

Sessions: The disease that had eaten her up and had -- it was a great moment in which the hope and everything she had suddenly -- the hope of her writing and everything -- suddenly hit her, that she just may never get to do what she wanted to do.

Sally: This was devastating knowledge.

She expected to live three years, which is what her father had lived after his disease was diagnosed.

Als: After she got sick, she was a prisoner of her body.

I think she loved writing so much because it freed her from the corporeal.

Gordon: I think that it's inevitable that her dark view of the body and not nature but the bodily world as being only a source of dark things, has to be connected to her lupus.

The deformed body, the broken body, the afflicted body is very much a theme that recurs in her work.

♪♪ McDermott: In some ways, I think we can say now thank God for her suffering, because it allowed her to produce the work that she produced.

O'Connor: To know yourself is to know your region and that it's also to know the world.

And in a sense, or paradoxically, it's also to be an exile from that world.

Smith: ♪ Lord, a good man is hard to find ♪ ♪ You always get another kind ♪ Sally: The first real story that was unquestionably carrying the power that she would later show.

Giroux: "A Good Man Is Hard To Find" changed her reputation.

♪♪ Gooch: Unlike what happened with "Wise Blood" which was incomprehension -- They had to go through several printings.

She comes to New York, is interviewed on television, the kind of new popular medium.

And has these great, glowing reviews in the New York Times, and this really establishes her then as an important American writer and especially a writer of her signature genre, the short story.

[ Typewriter clacking ] ♪♪ O'Donnell: They're on their way to Florida for vacation.

And the grandmother is sitting in the back seat with her two grandchildren.

[ Baby sputters ] "Tennessee is just a hillbilly dumping ground," John Wesley said.

"And Georgia is a lousy state, too."

O'Connor: Outside of Toomsboro, she woke up and recalled an old plantation that she had visited in this neighborhood once when she was a young lady.

"Oh, look at the cute little pickaninny," she said, and pointed to a Negro child standing in the door of a shack.

"Wouldn't that make a picture, now?"

she asked.

Brown: The grandmother, who in a sense is the central character in the story, her vanity which literally causes the catastrophe.

O'Connor: "It's not much farther," the grandmother said.

And just as she said it, a horrible thought came to her.

The thought was so embarrassing that she turned red in the face, and her eyes dilated, and her feet jumped up, upsetting her valise in the car.

The instant the valise moved, the newspaper top she had over the basket under it rose with a snarl, and Pitty Sing the cat sprang onto Bailey's shoulder.

[ Crashing ] [ Crow cawing, baby crying ] "We've had an accident," the children screamed in frenzy of delight.

"But nobody's killed," June Star said with disappointment.

The horrible thought she had had before the accident was that the house she had remembered so vividly was not in Georgia but in Tennessee.

In a few minutes, they saw a car some distance away on top of a hill, coming slowly as if the occupants were watching them.

The grandmother stood up and waved both arms dramatically to attract their attention.

Sally: Because she had seen newspaper accounts of The Misfit and most of the other figures.

O'Connor: "You're The Misfit," she said.

"I recognized you at once."

"Yes'm," the man said, smiling slightly, as if he were pleased in spite of himself to be known.

"But it would have been better for all of you, lady, if you hadn't a recognized me."

Als: And he's going to shoot her.

But she said, "I know you're not common and ordinary.

I know you're a good man."

O'Connor: There was a piercing scream from the woods, followed closely by a pistol report.

[ Woman screams, gunshot ] "Lady," The Misfit said, looking far beyond her into the woods, "there never was a body that gives the undertaker a tip.

Jesus was the only one that ever raised the dead," The Misfit continued, "and he shouldn't have done it.

He thrown everything off balance.

If he did what he said, then it's nothing for you to do but throw away everything and follow him, and if he didn't, then it's nothing for you to do but enjoy the few minutes you got left the best way you can, by killing somebody or burning down his house, or doing some other meanness to him.

No pleasure but meanness," he said.

Walker: He's shot everybody else, and he's about to shoot the grandmother.

And for the first time in her life, she gets it.

O'Connor: "Why, you're one of my babies.

You're one of my own children."

She reached out and touched him on the shoulder.

The Misfit sprang back as if a snake had bitten him and shot her three times through the chest.

Sally: And she dies quite happily.

Flannery, of course, insisted that this is a story about grace, a woman's sudden realization of her kinship with a criminal.

Rodriguez: The moment of violence is not where we recoil from each other, but when we are connected to each other.

Karr: "Take her off and throw her where you'd thrown the others," he said, picking up the cat that was rubbing itself against his leg.

O'Connor: "She was a talker, wasn't she?"

Bobby Lee said, sliding down the ditch with a yodel.

Wolff: "She would of been a good woman if it had been someone there to shoot her every minute of her life."

And, well, most of us would be.

[ Laughs ] [ Birds chirping ] ♪♪ ♪♪ [ Birds cawing ] Breit: I understand you're living on a farm.

O'Connor: Yes, I only live on one, though.

I don't see much of it.

I'm a writer, not far from the rocking chair.

♪♪ ♪♪ [ Bird honking ] ♪♪ ♪♪ Gooch: Because she was ill and she was on crutches, everything had to be precise.

There was only so much energy that could be given.

Frances: I knew Flannery for quite a while when she was ill, and I -- She was on crutches.

And I never heard her complain.

She was very adept at getting around on them.

I never saw her wince in pain.

She just was, as far as I could see, always in a good humor.

Steenburgen: I'm making out fine, in spite of any conflicting stories.

I have enough energy to write with, and as that is all I have any business doing anyhow, I can, with one eye squinting, take it all as a blessing.

[ Indistinct conversations echoing ] Sessions: Flannery worked every morning, from -- I guess she started around 9:00.

But you couldn't go there before 11:30.

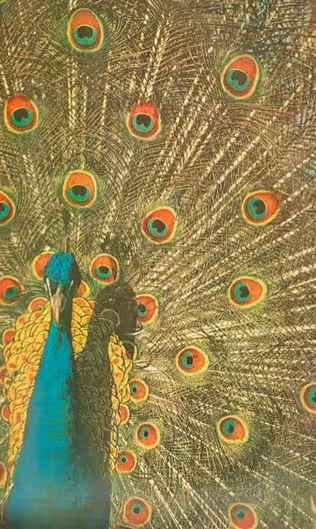

Giroux: While I was staying at Andalusia, the farm in Georgia, where Flannery lived with her mother and needed her mother -- Her mother, you know, took care of her -- I of course learned a great deal about peacocks, because there were certainly 40 or 50 peacocks on the farm.

[ Peacocks cawing ] I had a camera, and I said, whenever they saw my camera they'd start to pose.

They're real [Laughs] They're movie stars, you know.

And she said, "I know they're stupid and all," she said, "but they have a lot to be proud of."

[ Peacocks cawing ] ♪♪ Abbot: Neither Flannery nor Regina ever expected to have to live together as adult women.

Such a complicated relationship.

♪♪ Sally: She was considered an eccentric.

And yet, she was Miss Regina's daughter, and her manners were perfect, and they couldn't quite reconcile these two figures.

Giroux: Mrs. O'Connor said to me, "Mister Giroux, can you -- Why can't you get Flannery to write about nice people?"

I look at her, and I started to laugh.

Then I looked at Flannery, absolutely poker faced.

So I didn't laugh.

Her mother really was disappointed that her daughter was not a Southern belle.

Instead, she was a writer.

[ Cheers and applause ] Gentry: She had to, you know, face Regina at the dinner table, who was still waiting for her to come out with "Gone with the Wind 2."

Coonrod: From what I understand, she couldn't stand that movie when she was 14.

Walker: Her mother was such a classic, closed-mind Southerner of that era.

I feel, though, that Flannery had a great subject there and that she did a lot of examination of that particular personality.

[ Typewriter clacking ] Mrs. McIntyre: For years, I've been fooling with sorry people.

Sorry people, poor white trash and n[bleep].

They drain me dry.

Gooch: "The Displaced Person" is about an immigrant family from Poland, postwar refugees... ...who move into the South.

Astor: Who they, now?

Mrs. Shortley: They come from over the water.

Only one of them seems like can speak English.

They're what is called displaced persons.

Giroux: Regina never dreamed that she was a character in all of the stories.

The stupid woman was herself.

Boyagoda: Slowly but surely, the father figure for this refugee family starts to kind of take over the farm.

Mr. Guizac: Screw?

♪♪ Als: The violence in the stories was something that was always clear to me as a symbolic act leading to transformations.

♪♪ ♪♪ Abbot: Even though she is recognizable in Mrs. McIntyre, Regina was not contained in those characters.

[ People sobbing ] Boyagoda: You want some kind of clear resolution of all these different conflicts, and she denies it to us.

Steenburgen: I'm always irritated by people who imply that writing fiction is an escape from reality.

It is a plunge into reality, and it's very shocking to the system.

Wolff: But she's funny.

She's really funny, and she's often funny in a very dire way.

The laughter is the laughter of the skull of the memento mori on your desk.

[ Indistinct conversations ] [ Knife whooshes, thuds ] [ Children gasping ] ♪♪ Walker: I didn't realize that Flannery O'Connor lived across the way from us for many, many years.

It was one of my brothers who took milk from her place to the creamery in town.

When we drove into Milledgeville, the cows that we saw would have been the cows of the O'Connors.

But of course in '52, there was the same racism that had always been there.

[ Indistinct conversations ] Sessions: The issue of segregation was very much in the air.

♪♪ Milledgeville had an enclosed society.

They lived in terms of the institutions that were there.

Lee: When you said you were from Milledgeville, everyone would laugh and say, "Oh, you're one of those crazy --" You know, it was sort of like Milledgeville was synonymous with the state hospital.

♪♪ Abbot: Gothic.

♪♪ Grotesque.

♪♪ This small world.

A world that was circumscribed within a farmhouse, a farm, the surrounding countryside.

[ Rain pattering ] So much could happen in that world.

[ Thunder rumbling ] ♪♪ Breit: Do you have a fixed pattern of work?

O'Connor: Yes, I work every morning.

Breit: And you don't miss a day?

O'Connor: No.

Not even Sunday.

Breit: Intense.

I remember that Tomas Mann once said that he hated writing, that it was a trap that he had fallen into.

Do you feel that at all?

O'Connor: Well, I think you hate it and you love it, too.

It's something that, when you can't do anything else, you have to do that.

Woman: We have a good set of niggers here.

And they don't want to be disturbed.

I have one that I just love.

She nursed my children for about six years.

Of course, there are some getting some ideas, and that's all right.

That's progress.

♪♪ Rodriguez: Part of my worry as her reader is that she's too good, by which I mean that her mimicry of her voices around her is too acute.

In that accuracy, she doomed herself, because a lot of these stories are judged by modern readers as unacceptable.

Male reporter: Georgia tele-news cameraman unable to use -- Man #4: I don't associate with n[bleep], but on the other hand, I don't associate with common white trash or Jews or Catholics, if I can help it.

♪♪ Als: She's a brilliant reporter about the ways in which the social order was changing.

Over and over again in her stories, she was showing the disruption of the fantasy of whiteness, the fantasy of power.

Gentry: I think Flannery was writing for people who have been racist for a long time, and they know there's something wrong with that.

Als: I don't think Flannery was racist so much as she has a knee-jerk reaction to race in the way that she had a knee- jerk reaction to her mother.

Mrs. Shortley: I expect that before long, there won't be no more n[bleep] on the place, and I'll tell you what, I'd rather have n[bleep] than them Poles.

[ Indistinct conversations ] [ Geese honking ] Rodriguez: Around 1954, she met Erik Langkjaer.

Sally: Who had grown up in Denmark, decided to come to this country.

He was very much interested in religious matters, but he was far from being a Catholic.

Langkjaer: I was working for Harcourt Brace as a college textbook salesman.

And I had the whole of the South east of the Mississippi as my territory.

Sally: And one of his stops along the way was Georgia College in Milledgeville.

And when he was there, on his first visit, he went out to meet Flannery.

They became fast friends.

Rodriguez: Erik Langkjaer, tall, very learned and interesting young man, develops this fascination from his side with O'Connor.

This chance to have these kinds of conversations with a handsome young man were very important to her.

Gordon: He liked her very much, and they had clearly a kind of affinity, and he perceived that her life was very limited, and so he would take her out for rides.

Rodriguez: This relationship has a romantic aspect to it.

One of the women who worked on the farm said to someone else who worked there, "That's her boyfriend.

They're going out on a date."

Langkjaer: I had to completely rearrange my itinerary so as to be able to end up in Milledgeville as often as possible on weekends.

Rodriguez: On his last time before he's going off to Europe for the summer, they go for a ride in his car.

Langkjaer: I may not have been in love, but I was very much aware that she was a woman.

I felt that I'd like to kiss her, which I did.

♪♪ I was not by any means a Don Juan, but in my late 20s, I had of course kissed other girls.

And there had been this firm response which was totally lacking in Flannery.

I'd had a feeling of kissing a skeleton, and it reminded me of her being gravely ill. Gordon: He loved her.

He revered her particularly as a writer, but he was very freaked out.

He then left the country, went back to Denmark.

Sally: Then ensued a number of letters from Flannery, about 13, which are very revealing.

Steenburgen: Dear, dear Eric, you're wonderful and wildly original.

Did I tell you I call my baby pea chicken Brother in public and Erik in private?

Sally: In the course of time, he wrote announcing his engagement.

Flannery felt this disappointment very deeply.

Her mother had never mentioned Erik Langkjaer to me.

But we were old friends, and I was able to push her a little bit, and I said, "But did she suffer, Regina?

Did she suffer over this?"

And she looked down, and against her customary reserve, she was able to say, "Yes, she did.

It was terrible."

♪♪ Gooch: She has a terrible emotional personal reaction, but also a literary reaction which is, in four days, which is almost record time for O'Connor, who was known as a demon rewriter, she writes "Good Country People," a story that in some way metaphorically is about this relationship.

Steenburgen: "Good Country People" is a story of an unhappy woman with a wooden leg from a hunting accident.

Her given name was Joy, but she changed it to Hulga just to spite her mother.

One day, a traveling Bible salesman comes to her door.

Sally: Eric's lists from Harcourt Brace, he called the Bible.

Gooch: In the hayloft on the farm that's exactly a replica of Andalusia, the O'Connor's farm, she has this kind of flirtation with the Bible salesmen.

Langkjaer: Reading it, I realized right away that here I was in some sort of disguise.

[ Typewriter clacks, dings ] Wolff: "Come on now.

Let's begin to have us a good time.

When ain't got to know one another good yet."

[ Rooster crows, clucks ] "Give me my leg," she screamed and tried to lunge for it, but he pushed her down easily.

"What's the matter with you all of the sudden," he asked, frowning as he screwed the top on the flask and put it quickly back inside the Bible.

"You just awhile ago said you didn't believe in nothing.

I thought you was some girl."

"Give me my leg," she screeched.

He jumped up so quickly that she barely saw him sweep the cards and the blue box into the Bible and throw the Bible into the valise.

And then the toast colored hat disappeared down the hole and the girl was left sitting on the straw in the dusty sunlight.

When she turned her churning face toward the opening, she saw his blue figure struggling successfully over the green speckled lake.

[ Water sloshing ] You know, as Dostoevsky said, "Without God, everything is permitted."

♪♪ Steenburgen: Dear Eric, I'm highly taken with the thought of you seeing yourself as the Bible salesman.

Dear boy, remove this delusion from your head at once.

Never let it be said that I don't make the most of experience and information, no matter how meager.

♪♪ Brenda Lee: ♪ Well, now just because you think you're so pretty ♪ ♪ Just because you think you're so hot ♪ ♪ Just because you think you've got something ♪ ♪ Nobody else has got ♪ Breit: I for myself think that although Ms. O'Connor can be called a Southern writer, I agree that she's not a Southern writer, just as Faulkner isn't, and that they are, for want of a better term, universal writers.

They're writing about all mankind and about relationships and the mystery of relationships.

And I'm relieved that you write as simply as you do.

Gooch: So, after the disruption of her relationship with Eric and also then the publication of "A Good Man Is Hard to Find," she develops different sorts of relationships.

The kind of friendship with Maryat Lee, the bisexual sister of the President of the Georgia State College for Women, comes to see her.

And Maryat Lee is living in Greenwich Village and an unlikely, eccentric looking woman in the middle of Georgia, walking around in boots and a cape and things like that.

But again, the two hit it off.

Coonrod: She shows, first of all, her tremendous generosity and her -- the gameful spirit, you know, especially with Maryat Lee, just hilarious spirit.

Lee: Maryat's very being kind of buttressed Flannery's.

Okay, you know, there's another one out there.

♪♪ Abbot: She could scowl as effectively as anybody I've ever known.

One of the few signs of Flannery's lupus was the fact that after the midday meal, you could see her tiring.

The cortisone derivative that she took, which saved her life, had softened the bones and also had put her on crutches, and this had altered her appearance.

But she was wonderfully animated when she was interested in what she was saying, when a good question was asked and she could answer with zest.

Steenburgen: If the fact that I'm a celebrity makes you feel silly, what, dear girl, do you think it makes me feel?

It's a comic distinction shared with Roy Rogers' horse and Miss Watermelon of 1955.

Sally: Betty Hester appeared at a point in Flannery's life where she had just had a bit of disappointment and realized that she was going to be alone for the rest of her life, that her life was going to be writing.

And she needed conversation.

And suddenly, she received a letter from a complete stranger in Atlanta who seemed to realize that these stories, as she put it, are about God.

And Flannery said, "Who is this who understands my story?"

Steenburgen: I'm very pleased to have your letter.

Perhaps it is even more startling to me to find someone who recognizes my work for what I try to make it than it is for you to find a God-conscious writer near at hand.

The distance is 87 miles, but I feel the spiritual distance is much shorter.

Sally: There began a conversation that lasted for years, by letter.

They wrote every two weeks, Betty Hester was a clerk in a credit office.

Sessions: Betty was lesbian and had actually suffered horribly for that.

I mean, she was in the Air Force, and she was kicked out and had to go back to 1950s South where it was hard for a woman period to get a job.

And if your service record said something, you may as well go back to the penitentiary.

She lived in fear from that time on.

She had no relationships with anybody.

She lived with her aunt.

Sally: She had a dingy, little job, and her whole life was reading.

And the letters that she elicited from Flannery are among the real treasures to be found in Flannery's letters.

Steenburgen: I find myself in a world where everybody has his compartment, puts you in yours, shuts the door, and departs.

My audience are the people who think God is dead.

At least these are the people I am conscious of writing for.

Gooch: Then Betty Hester, she writes a letter of almost confession to Flannery O'Connor about the lesbian activities that had caused her to be discharged from the military.

When you're reading this exchange of letters between them, I was on the edge of my seat, because you're wondering where O'Connor is going to go with this.

I mean, she could go almost either way.

Steenburgen: Betty, I can't write you fast enough and tell you that it doesn't make the slightest bit of difference in my opinion of you, which is the same as it was, and that is based solidly on complete respect.

You've done me nothing but good.

But the fact is above and beyond this that I have a spiritual relationship to you.

What is necessary for you to know is my very real love and admiration for you.

Yours, Flannery.

Gentry: Flannery's letters were her closest relationships with other human beings.

♪♪ Michael: "The Habit of Being" opened that door so that people understood that this woman had a religious point of view, that she saw life as the action of God's grace and that without understanding that, it's impossible to know what she was doing and what those stories really mean.

Jones: That's the whole point of her writing, I think, the Catholic thinking, not be so doctrinaire that she reveal it to be obvious to feeling and thinking people.

♪♪ Rogers: ♪ Wildcat Willy, looking mighty pale ♪ ♪ Was standing by the sheriff's side ♪ ♪ And when that sheriff said, "I'm sending you to jail" ♪ ♪ Wildcat raised his head and cried ♪ ♪ O give me land, lots of land, under starry skies above ♪ ♪ Don't fence me in ♪ ♪ Let me ride through the wide open country that I love ♪ ♪ Don't fence me in ♪ ♪ Let me be by myself in the evening breeze ♪ ♪ And listen to the murmur of the cottonwood trees ♪ ♪ Send me off forever but I ask you please ♪ ♪ Don't fence me in ♪ Baldwin: Why do you have to fight for your civil rights?

If you're fighting for your civil rights, that means you're not a citizen.

Sally: There was a famous incident that's been cited a good deal when Flannery was invited by Maryat Lee to meet James Baldwin.

She offered to arrange a meeting when Baldwin was traveling through Georgia.

And Flannery declined this meeting, although she was careful to say that she would be delighted to meet James Baldwin anywhere else, but she would not meet him in Milledgeville.

Steenburgen: In New York, it would be nice to meet him.

Here, it would not.

I observe the traditions of the society I feed on.

♪♪ Might as well expect a mule to fly as me to see James Baldwin in Georgia.

Als: She didn't want to be a spokesman for the South.

She was an artist.

She could only talk about the South if she was one of its citizens.

If they met in Georgia, it would be a civil rights cause, and she would not be able to live in that town unobserved.

And that was the whole point of writing for her was to be almost a reporter.

♪♪ Sessions: Flannery was crippled.

Flannery was sick.

She couldn't say, "I'm out of here.

I'm out" -- "Where are you going, Flannery?

Where are you going to get the money?"

They had no money.

I mean, Flannery didn't make any money from her books.

That's why she went out on speaking tours.

Steenburgen: Next week, I go to Rosary College in Chicago and then to Notre Dame.

Then I have to go to Emory and talk to a Methodist student congregation on the South, their choice of topic.

A little of this "honored guest" business goes a long way, but it sure does help my finances.

Sally: Maryat Lee poked fun at Flannery's religion, and Flannery poked fun at Maryat's activism.

Flannery addressed her friend Maryat as "Dear nigger loving New York white woman."

It was the New York white woman that was the hidden insult, but it has been held up as an example of Flannery's errant racism.

Walker: If you just see the Southern writers, generally white Southern writers, on the basis of more or less their racism, which is there -- Nobody should be locked into ideologies that they were born into and that they often were not even able to see.

So the writers get sold.

They get sold down the river, too.

♪♪ [ Birds chirping ] [ The Singing Nun's "Dominique" playing ] ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ Sally: Flannery had been ill so long and her prospects were so dim, cousin Katie wanted her to go to Lourdes.

Flannery very reluctantly agreed.

She said, "I don't want a miracle.

I've come to terms with my life.

I don't want a miracle.

I want to go right on doing what I'm doing.

But she didn't like to disappoint her cousin.

Announcer: Without cessation, throughout the day at Lourdes, 60,000 pilgrims attended or heard divine services.

Many will have been ill and beyond medical aid, but hoping to show on their return that their faith has made them whole.

Sally: Of course, there were many people there, sick, the lame, the halt, and the blind were there and everyone full of hope.

And it was very touching.

It was very moving.

But Flannery was still very reluctant to take the bath.

She said, "I'm the kind of Catholic who could die for her faith before she would take a bath for it."

[ Indistinct conversations ] Sessions: For a while, it looked as though something had really happened, because about six months later, Regina said to me in an aside, she said the hip had begun to re-calcify and so forth.

Of course it didn't last.

♪♪ Steenburgen: I have a large tumor, and if they don't make haste and get rid of it, they will have to remove me and leave it.

♪♪ Abbot: She had surgery the next day, and I had a note from her, when she could write, saying that the surgery was a howling success.

The operation may have been a howling success.

The lupus came howling back.

Giroux: I was working with a dying writer.

I know it.

We're putting together her last book, "Everything That Rises Must Converge."

She was in the hospital in Atlanta.

It was -- In a way, it was a kind of a horror story, because she was so anxious to get the last story, "Revelation."

She wanted that to get in.

♪♪ Rodriguez: There is this wonderful short story about these people in a waiting room of a doctor's office.

[ Man coughing, baby babbling ] This young woman with this garish face who is angry at the woman who was sitting across from her, Mrs. Turpin.

Black delivery man who comes in.

Steenburgen: "They ought to send all them niggers back to Africa," the white trash woman said.

"That's where they come from in the first place."

"Oh, I couldn't do without my good colored friends," the pleasant lady said.

[ Telephone rings ] "There's a heap of things worse than a nigger," Mrs. Turpin agreed.

"There's all kinds of them just like there's all kinds of us.

It wouldn't be practical to send them all back to Africa.

They've got it too good here."

Sessions: Good satire always has a center.

And she has a center.

It's a center so profound that she can see everything as distorted and very funny.

Lee: Flannery made Mary Grace this person with a sense of rage that was building.

[ Book clatters, telephone rings ] Steenburgen: Go back to hell where you came from, you old wart hog.

[ Glass shatters ] [ Woman gasping, telephone ringing ] Lee: "Revelation" was a bowing of Flannery to Maryat's concern that she not dress or reference issues of race.

You know, Maryat went to Wellesley, Mary Grace went to Wellesley.

The last letter that Flannery wrote before she died was to Maryat, which I think is a testament to the kind of closeness they had.

Steenburgen: Sometimes Mrs. Turpin occupied herself at night naming the classes of people.

On the bottom of the heap were most colored people -- not the kind she would have been if she'd been one, but most of them.

Then next to them, not above, just away from, were the white trash.

[ Keys jingling ] Then above them were the homeowners.

And above them, the home and landowners, to which she and Claud belonged.

Usually by the time she'd fallen asleep, all the classes of people were moiling and roiling around in her head, and she would dream they were all crammed in together in a boxcar being ridden off to be put in a gas oven.

[ Train wheels clacking ] ♪♪ Louise: She always worked.

As long as she was able to work, she worked.

Even in the hospital, she was making notes or observations, certainly.

McDermott: The sun was behind the wood, very red, looking over the paling of trees like a farmer inspecting his own hogs.

"Why me?"

she rumbled.

"It's no trash around here, black or white, that I haven't given to.

And break my back to the bone every day working.

And do for the church.

Go on!"

She yelled, "Call me a hog.

Call me a wart hog from hell.

Put that bottom rail on top.

There'll still be a top and bottom."

A final surge of fury shook her and she roared, "Who do you think you are?"

[ Chuckles ] It's so good.

♪♪ ♪♪ Louise: We found a calendar in Regina's room, and it was turned to August of '64.

And on the day Flannery died, Regina had written, "Death came for Flannery."

Michael: I'm really sorry she died at the age of 39.

I think that both my parents thought that she was with God, so it was okay.

Gordon: She looks at the darkness unflinchingly, and she approaches it with clarity and with precision.

And that I think is her greatness.

Sally: I feel that Flannery O'Connor's life and Flannery O'Connor's work were all of a piece.

They were both returns of her gifts, her talents.

She considered her faith a gift.

She considered her talent a gift.

And she wanted to return them with gain.

And I think she did.

I think her life is almost as imposing as her work.

♪♪ Jones: She's one of the best writers of the 20th century.

I've read everything that she's written.

♪♪ Sessions: The life of Flannery O'Connor and what she had to offer, in terms of her relationship to the greater mysteries of existence, are going to be things that people will tap into, because they aren't going away.

Gordon: At length, she got down and turned off the faucet and made her slow way on the darkening path to the house.

In the woods around her, the invisible cricket choruses had struck up, but what she heard were the voices of the souls climbing upward into the starry field and shouting hallelujah.

[ Footsteps, crutches clicking ] [ Insects chirping ] ♪♪ [ Bruce Springsteen's "Nebraska" playing ] ♪♪ ♪♪ Announcer: To order "Flannery" on DVD, visit ShopPBS or call 1-800-PLAY-PBS.

This program is also available on Amazon Prime Video.

Springsteen: ♪ ...her baton ♪ ♪ Me and her went for a ride, sir ♪ ♪ And ten innocent people died ♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: 3/23/2021 | 1m 54s | Explore the life of Flannery O’Connor whose fiction was unlike anything published before. (1m 54s)

From the Director: The Making of Flannery

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 3/23/2021 | 2m 18s | Hear from director Elizabeth Coffman about the making of American Masters: Flannery. (2m 18s)

Why did Flannery O'Connor detest "Gone with the Wind"?

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 3/23/2021 | 2m 41s | She reportedly “couldn’t stand” the romanticized, Hollywood version of the old South. (2m 41s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Support for American Masters is provided by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, AARP, Rosalind P. Walter Foundation, Judith and Burton Resnick, Blanche and Hayward Cirker Charitable Lead Annuity Trust, Koo...